Biomimicry in Architecture

Biomimicry is not for those who are pleased with the status quo. It’s for the industry practitioners who are searching for more efficient, more sustainable, healthier and safer solutions when it comes to constructing a building.

In Greek, bios means “life”, and mimesis means “imitate”. Thus, biomimicry in architecture means imitating life to solve design and building problems.

The term was coined by Janine Benyus in her book Biomimicry—Innovation Inspired by Nature. A design discipline now, biomimicry investigates “how living organisms create and solve design challenges”.

As Benyus states in her TED talk, “we are not the first builders”. Far from it.

Nature has been devising, testing, and adapting solutions for more than 3.8 billion years now. That’s a huge amount of experience. Should we reject the opportunity to learn from such an expert?

Before you get down to your next building project, let’s find out how nature helps to push and pull the boundaries of building design.

Meeting And Fighting The Challenge

Costly and resource-hungry solutions have been a norm in architecture for a long period of time.

Nature, however, has chosen a different path. It relies on the properties of material and finds the best possible option to use. Look around. Animals, plants and other organisms “have engineered themselves to survive and thrive this far” without producing any waste.

True, nature has had millions of years to perfect its craft. But that does not mean we should sit with folded hands.

How to turn waste into food? How to recycle and give back to nature with zero negative footprint? How to capture and store sunlight? How to cool and heat a shelter? How to ensure the safety and health of occupants? How to come up with a design that’s adaptive rather than resistant to change?

If you look closer, you will see that these questions lie at the heart of any sustainable building project.

Learning From Nature’s Engineering Genius

On one hand, shapes and forms found in nature can hint you a specific design solution.

A case in point: Antoni Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia is a breathtaking example of how a forest can inspire a magnificent building. The 150-foot tall vault is supported by tree canopies while the huge trunks carry the load of the building. As you enter this Roman Catholic Church, an enormous forest welcomes and embraces you. A vision Gaudi intended to bring to life.

Image source: Spain then and now

On the other hand, nature educates you about processes and systems to help you do more using less. In this case, you are given an opportunity to “translate characteristics from biological systems to building design”.

Let’s find out what happens when designers, engineers, builders, and architects invite nature to the design table.

● Using CO2 To Make Cement

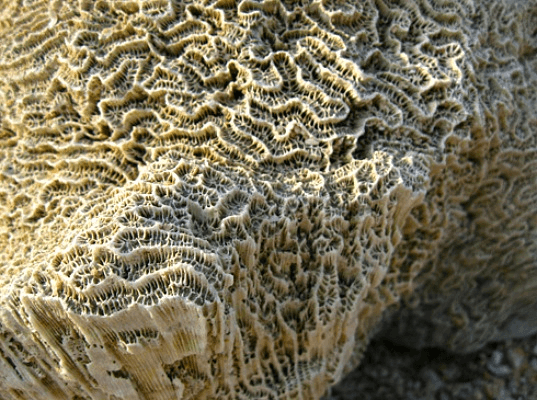

Have you ever wondered how coral reefs are constructed? It turns out, when CO2 gas and ocean water come into reaction, coral structures are created.

Image source: Inhabitat

Brent Constantz, a bio mineralization expert from Stanford University, observed the process of mineralization and used CO2 for concrete production.

Biomimicry, thus, helped to come up with a technology that uses waste as raw material and reduces the carbon footprint in an emission-intensive process — cement production.

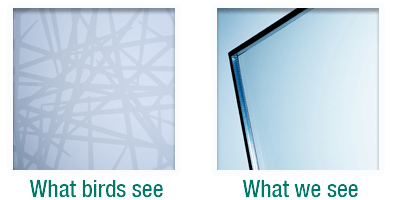

● Glass That Integrates Reflective UV Component

As more and more buildings with glass facades started to rise, people were left facing a sad reality: the reflective glass has been a fatal solution for millions of birds each year. Birds are misled by the reflections of trees and landscapes in windows and are killed when they fly into the glass.

Image source: ORNILUX

Image source: ORNILUX

Using the principles of biomimicry, the Arnold Glas Company found a solution after studying spider webs and how they avoid destruction by bird flight.

Interestingly, spider webs include “a reflective component in the UV range that deters birds from flying into their webs”. At the same time, they attract moths and other insects towards their reflective light. Inspiring, isn’t it?

● Self-Cleaning Facades

Cleaning building exteriors is a labor, water and chemically-intensive task. But what if building facades could self-clean?

This was a challenge a Japanese company LIXIL tried to fight. Snail shells readily solved the riddle. They have microscopic pools that lock in moisture making it possible for them to self-clean. The bumps are formed owing to silica, an element naturally found in soil.

LIXIL created exterior wall coating that contains silica. Every time it rains, the walls are washed clean of pollutants and exhaust.

The list on nature’s engineering genius can go on endlessly, but we will stop here to take you on a tour to three buildings in Singapore, USA, and the UK. These buildings are living examples of how nature can inspire unique solutions of design.

Buildings Inspired By Biomimicry

1. The Esplanade Theatres

Building Skin Becomes An Efficient Shading

Durian is widely known and used in Singapore. It’s a tropical fruit – a source of both income and nutrition for local people.

This fruit features a thorn-covered husk to keep the seeds safe from extreme heat — a function that inspired the design of the Esplanade Theatres.

The skin of the building has three main benefits: it adjusts to the environment by letting sunlight in, protects the interiors from overheating, and gives people an opportunity to admire the outside view.

Image source: DP Architects

After studying the solar path over the building, it was decided to choose external fins (shields) that vary in geometry and respond to the angle of the sun by changing their shape and orientation.

Add to this the geometry of a mesh covering the dome of the building, and here you have a giant fruit that solves a major design challenge for a building located so close to the equator

Image source: DP Architects

But sometimes, design comes at a cost for maintenance. In case of the Esplanade, each spike is cleaned by hand, and the two domes require approximately two months to be cleaned.

Image source: Esplanade

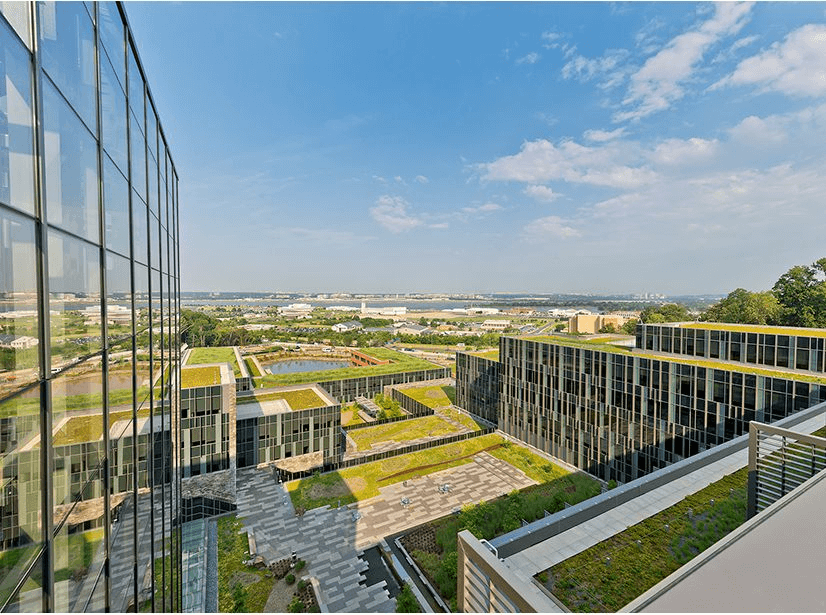

2. U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters.

Layered Rooftops Provide An Efficient Water Management System.

A building, located in Washington D.C., boasts it ability to cleanse and use rainwater for rooftop vegetation.

The inspiration? Beavers (the second-largest rodent in the world, known for building dams and canals) and the process they use to slow, store and clean water by building layered dams.

The rooftops of the U.S. Coast Guard Headquarters are all connected to one another creating a system similar to what beavers build. When it rains, water goes down. The unique construction of the landscape and a set of terraces use the force of gravity to move and capture water in a huge pond. Stormwater is then cleansed and reused to water the green roofs – 550,000 square feet in total!

Image source: Greenroofs

Image source: Greenroofs

Imagine if such techniques were implemented at a larger scale worldwide. We would certainly create opportunities for more sustainable water management both in rural and urban communities.

3. The Gherkin.

The Shape Of The Building Ensures A Highly Efficient Ventilation

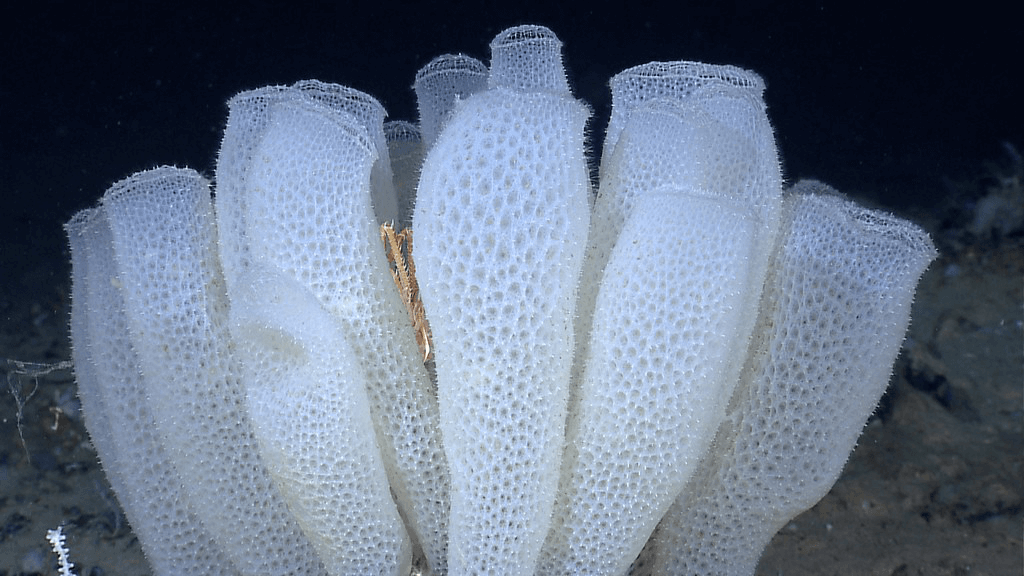

The UK’s 180m skyscraper has an air ventilation system that makes it possible for air to flow through the entire building. It uses a similar principle that sea sponges and anemones use: they “feed by directing sea water to flow through their bodies”.

Image source: The American Academy of Achievement

“The Gherkin”, officially known as 30 St Mary Axe, was designed by Norman Foster who took the inspiration from the Venus flower basket sponge.

Image source: Neri Architects

Image source: Neri Architects

The Gherkin responds not only to the air flow which increases owing to the cylinder shape of the building. It also “uses spiraling light wells and windows” which automatically respond to the flow of light by letting in fresh air to each floor. The result? Up to 40% reduction in energy costs per year.

What’s more interesting, the structure is freestanding: no columns inside. Uninterrupted office space is there to enjoy as soon as people get to work.

Image source: Neri Architects

Image source: Neri Architects

But there is more. The space between the double skin façade “contains venting flaps to allow hot air to travel up and out of the building”.

Now that we know biomimicry can help us solve architectural dilemmas, let’s open a toolbox to find esources for applying these techniques in your next design so that tomorrow’s buildings perform efficiently long after ribbon-cutting ceremonies.

Where To Start?

Look at nature as “model, measure, and mentor” – that’s what the Biomimicry Institute is advocating.

Founded in 2006, they developed Ask Nature – an open source project to help industry practitioners to get acquainted with design systems already existing in nature. Ask Nature provides access to strategies, blueprints, products, sketches as well as opportunity to talk to and collaborate with experts.

Biomimicry 3.8 is another rich community you would like to consider. It offers consulting, professional training, and inspiration and has designed a practical tool called Biomimicry Design Spiral that uses six steps to apply biomimicry in design: Define (Identify), Biologize (Translate), Discover, Abstract, Emulate, and Evaluate.

Image source: Biomimicry Toolbox

Image source: Biomimicry Toolbox

More resources about biomimicry can be found on the website of Whole Building Design Guide on the page Biomimicry: Designing To Model Nature.

Ready To Make The Switch?

Biomimicry is an emerging path in architecture and has a distance to walk to become a widely applied practice.

However, challenges we face today force us to produce buildings that are not only energy, water, and waste-efficient, but also give back to nature.

The job market will increasingly be in search for professionals who understand what high-performance design is and how to work with innovative systems and tools.

Knowledge, hands-on experience, competency, and leadership — you will need a rich background to become a sought-after specialist.

Back to Basics, a nationally recognized training provider, is here to help.

You receive high quality training at an affordable price and in the shortest time frame possible.

And that’s only the beginning.

- You enjoy the flexibility and efficiency of learning online.

- You gain access to training materials written by builders for builders.

- You receive one-on-one training from industry experts.

If you would like more information on the courses Back to Basics offers or are interested in upgrading your resume with one of our qualifications, call us on 1300 855 713 or email enquiries@backtobasics.edu.au to find out more.